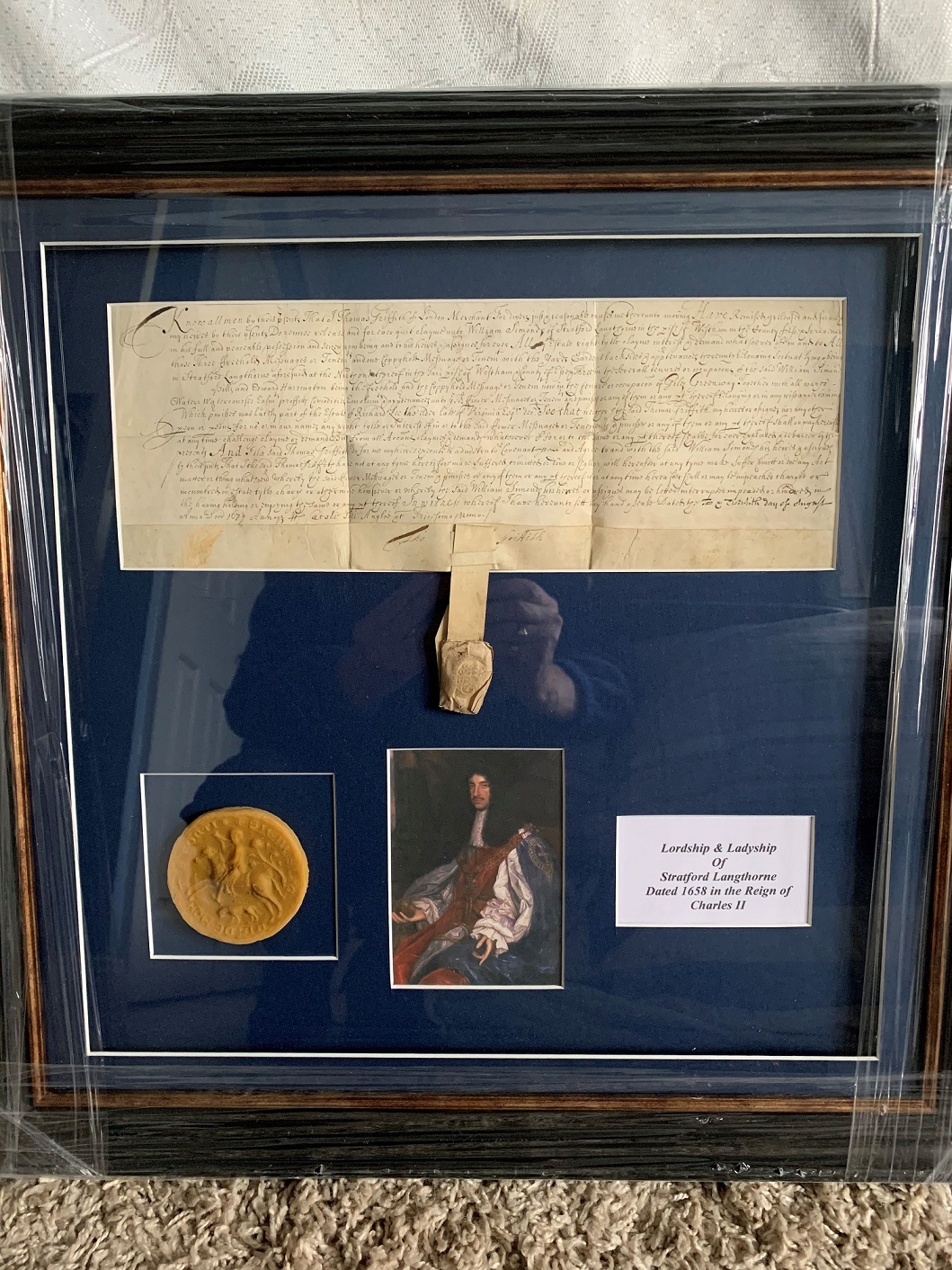

Lord & Lady of Stratford Langthorne (London) Rare

Price £64,000 Now £55,000

Special Notes:

- Held by Great Grandfather of General Robert E Lee.

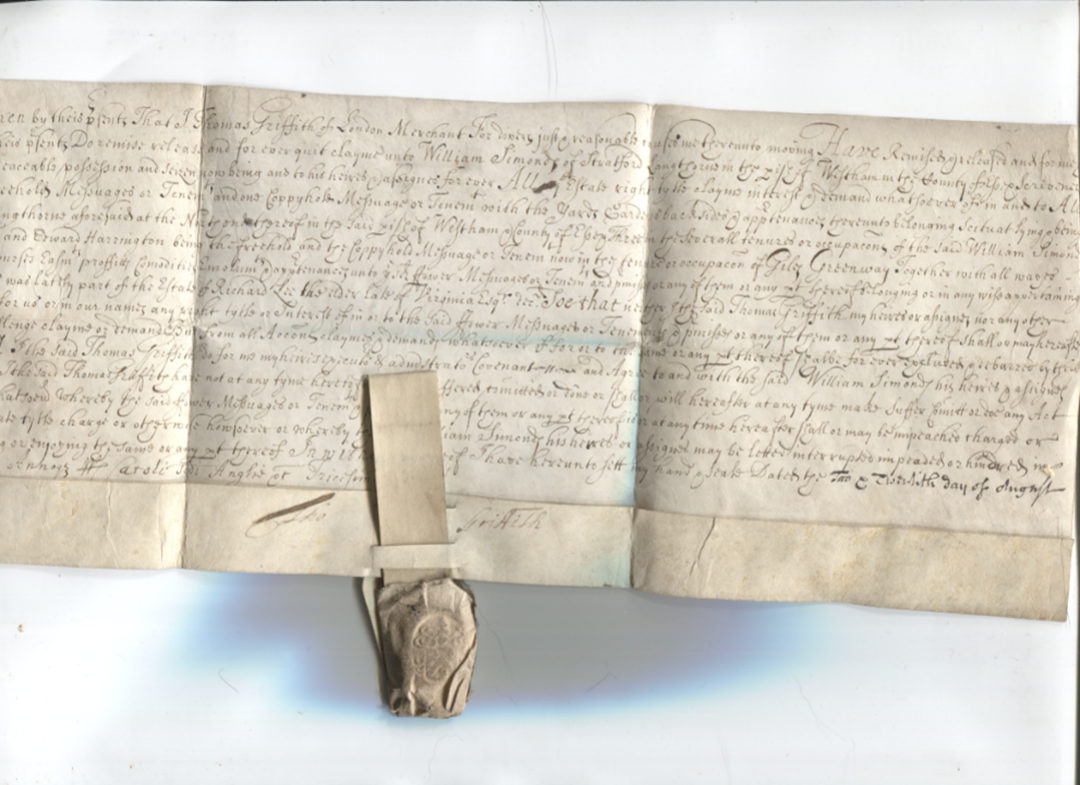

- With 343 year old original deed.

Held by Royalty:

- Henry I

- Henry VIII

Brief Description:

Lordship and Ladyship STRATFORD LANGTHORNE, West Ham, London Essex

Parties are Thomas Griffith, a merchant of London, quitting his claim to properties in Stratford-Langthorne, parish of West-Ham, Essex in favour of William Simonds of Stratford. Properties include copyhold messuage occupied by Giles Greenway and the estate of the deceased Richard Lee the Elder of Virginia. Stratford-Langthorne was a fashionable place for Londoners to stay at the time. Richard Lee bought the estate in 1658 for his family to stay in, having acquired vast plantations and slaves in America. His descendants include General Robert E. Lee. Francis Lightfoot and Richard Henry Lee were both signatories to the Declaration of Independence. dimensions are 36 x 13.5cm.

THE ABBEY OF STRATFORD LANGTHORNE (fn. 1)

Stratford, like Coggeshall, was a daughterhouse of the abbey of Savigny in Normandy. It was founded by William de Montfitchet (fn. 2) in 1135; the actual day of foundation, by which the assembly of the convent is probably meant, being given (fn. 3) as 25 July. The founder granted to the monks by charter all his lordship of (West) Ham, eleven acres of meadow, two mills by the causeway of Stratford, his wood of Buckhurst and the tithe of his pannage. The abbey was dedicated in honour of St. Mary.

Henry II by a charter in the latter part of his reign confirmed the grants by the founder and others, including the churches of West Ham and Leyton, of the grant of Gilbert de Montfitchet, and that of Greenford (Ilford), of the grant of Sybil the wife of Norman. Two charters were obtained from Richard I. By the first, on 15 September, 1189, he granted liberties, and by the second, on 7 December, 1189, he confirmed the possession of the churches of West Ham and Burstead and various lands, and granted licence to cut wood for fuel and building, pasture for eight ‘greater hundreds’ of sheep on the heath by Walthamstow, and liberties. Both charters were subsequently ratified by him under his later seal on 24 October, 1198. John on 3 June, 1203, granted licence for the enclosure of the wood of Buckhurst; (fn. 4) and in 1207 restored to them the land of ‘la Suthbir” in West Ham, which had belonged to John de Venicia, and which the king had granted away to Peter de Pratellis. (fn. 5) Henry III made a liberal grant to the convent on 14 May, 1253, of free warren in their demesne lands of West Ham, Leyton, Chigwell, Woodford, Mountnessing, Weald, Ingrave, Dunton, East Horndon, Chadwell, Little Thurrock, Great and Little Burstead, Ging Landry and Ging Joyberd, as well as licence to enclose a grove in Leyton, and a market on Tuesday at Great Burstead, and a fair there yearly on the vigil, the day and the morrow of St. Mary Magdalene. (fn. 6) All these grants were confirmed by Edward I and several later kings. (fn. 7) Edward IV on 23 July, 1468, granted to the convent two tuns of wine yearly for the celebration of masses, (fn. 8) but as they did not receive full payment of this an annuity of £10 was substituted on 19 March, 1479. (fn. 9) He also on 10 December, 1476, granted to them a market on Wednesday at Billericay, and two fairs of three days each there yearly at the feasts of St. Mary Magdalene and the Decollation of St. John. (fn. 10)

A fragment (fn. 11) of a register or ledger book of the abbey is preserved at Trinity College, Dublin, but it only contains some agreements with Halywell Nunnery of no great importance.

The temporalities of the abbey mentioned in the Taxation of 1291 amount to the considerable sum of £209 3s. 3½d. yearly. The chief contributions were £45 14s. 4d. from West Ham, £33 9s. 10d. from Great Burstead and £23 3s. 6½d. from Leyton; while £13 8s. 0d. came from Mountnessing, £12 19s. 0d. from Little Thurrock, £12 17s. 2d. from Chigwell and £11 12s. 0½d. from Ilford, and amounts of over £1 from a dozen other places, including £7 11s. 8d. from Lewisham in Kent and £1 12s. 0d. from Winkfield in Berkshire. The abbey also owned the rectories and advowsons of the vicarages of Great Burstead, West Ham, Little Ilford, Leyton and Great Maplestead. Licence was granted by the king in 1306 for the acquisition of the advowson of the church of East Ham, and on 9 April, 1309, (fn. 12) the church was appropriated to the abbey and a vicarage ordained by the bishop, who, however, reserved to himself and his successors the collation to the vicarage. Numerous acquisitions of property are recorded on the early Fines; and later, after the Statute of Mortmain, many licences to acquire lands appear on the Patent Rolls. Of these the most important is probably the licence granted to the abbot and convent on 15 March, 1319, to acquire the reversion of the manor of East Ham. (fn. 13) They appear to have entered on the manor without due process in Chancery, for in 1373 they had to pay £20 to obtain pardon for this trespass. (fn. 14) The manor of Burstead is mentioned in 1285 as having been granted to the abbey by Richard Siward, to whom it had previously been granted by William Marshal, earl of Pembroke. (fn. 15)

The abbot was charged with the repair of the bridges and causeway between Stratford-atte-Bow and Ham Stratford, as owner of the lands which had been granted by Maud, queen of Henry I, to Barking Abbey for that purpose. These lands were subsequently transferred to Stratford, and a dispute arose between the two houses about the obligation, which was settled in 1315 (fn. 16) in favour of the abbess of Barking, who however paid £200 to Stratford in recompense. The abbot had licence (fn. 17) on 3 January, 1317, to move sand and gravel from some parts of the highway to others for this repair. In 1691, long after the dissolution, it was decided in the King’s Bench that the tenants of these lands were liable for the same repair. (fn. 18) The abbot was also to a large extent responsible for the maintenance of the sea wall round the marshes of West Ham, and in 1280 (fn. 19) and 1292 (fn. 20) we find him complaining that other persons having land in the neighbourhood refused to make their proper contributions, while in 1339 he endeavoured unsuccessfully to put the whole burden of repairing one of the dykes in West Ham marshes on to the prioress of Stratford-at-Bow. (fn. 21)

Leland, (fn. 22) writing about the time of the dissolution, says ‘ This Howse first sett amonge the low Marsches was aftar with sore Fludes defacyd and removid to a Cell or Graunge longyng to it caullyd Burgestede in Estsex, a mile or more from Billirica. Thes monks remainid at Burgstede untyll entrete was made that they might have sum helpe otherwyse. Then one of the Richards, Kings of England, toke the Ground and Abbay of Strateford into his protection, and reedifienge it brought the forsayde Monks agayne to Stratford, where amonge the Marsches they reinhabytyd.’ This statement was probably made from tradition only, and it is not borne out by any existing documentary evidence, though it is by no means impossible. The Richard referred to must almost certainly have been Richard I, but neither in his charters nor in that of Henry II is there any indication of such removal.

But, however this may be, it is certain that at quite early times the abbey became prosperous; it was one of the richest (fn. 23) and, owing to its proximity to London, one of the most important of the order in England. In 1267 Henry III received the pope’s legate at the abbey and made peace with the barons there. (fn. 24) Henry IV was several times at the abbey in 1411 and 1412. (fn. 25) In 1501 the abbot was one of the people appointed to receive Katharine of Arragon; (fn. 26) and on 10 September, 1533, Abbot Robert, (fn. 27) with the abbots of Westminster, St. Albans and Bermondsey, assisted the bishop of London at the baptism of the Princess Elizabeth in the church of the Friars Minor at Greenwich. The abbot also assisted at the funeral (fn. 28) of queen Jane Seymour in November, 1537.

At the beginning of the reign of Edward I (fn. 29) the abbot and convent were considerably in debt to Elias son of Moses, a Jew of London, and Floria his wife and others, for lands bought in Mountnessing and various loans. The king, however, at the instance of his mother, Queen Eleanor, pardoned them all pains and usuries of these debts, provided that they satisfied the Jews of the principal. Inquiry was to be made as to the amount of the debt, and the charters whereby they were bound were to be withdrawn from the chest of the chirographers of the Jews and delivered to the abbot and convent. If the latter could show by stars or other instruments that they had repaid anything allowance was to be made to them accordingly.

Under Edward I and Edward II the abbot was summoned to Parliament, (fn. 30) though not on any subsequent occasion.

The abbot is often mentioned as going abroad, generally to the chapter general at Cîteaux, being allowed in 1316 (fn. 31) to take as much as £40 with him for his expenses. In 1345 (fn. 32) he went to Savigny to excuse himself from attendance at the next chapter general.

On 18 April, 1350, the king granted (fn. 33) protection for one year to the abbot, who at the command of his superior abroad was making a visitation of certain houses of the order in England and Wales. The abbot of Stratford, with the abbots of Boxley and St. Mary Graces by the Tower, held the provincial chapter of the order at London in 1395, (fn. 34) and Abbot Hugh as one of the conservators of the order was concerned in the deposition of the abbot of Buckland in 1470. (fn. 35)

Corrodies were claimed by the crown in the abbey. On 30 March, 1317, Master John de Sutton, the king’s cook, was sent (fn. 36) to the abbot and convent with a request that they would grant him maintenance in food and clothing and two robes yearly as for a servant, and maintenance for two grooms and two horses, and robes for the grooms of the suit of the abbot’s grooms, and that they would find him candles, litter, firewood, and all other necessaries, and assign to him a chamber in the abbey. But Richard II on 24 May, 1397, alleging that ‘William de Montfitchet, who began to found the abbey, died without heir before he could found it, so that the abbot and convent were destitute of a protector,’ granted (fn. 37) that he should be considered their founder, and they should be of his foundation and patronage; and they should have all liberties and franchises as other Cistercian houses, and should be quit of corrodies; and at voidance they should not seek licence before proceeding to election, and no escheator should meddle with the temporalities; and they should not be made collectors of tenths, etc. This grant may perhaps be the foundation of Leland’s statement. The last clause, of exemption from collection, was revoked (fn. 38) on 8 May, 1401, at the supplication of the bishop of London, who represented that it would be to the prejudice of the king and prelates and a pernicious example.

The abbey suffered from the insurrection of the peasants in 1381, its goods being carried off and its charters burned. A commission was appointed (fn. 39) on 7 August to inquire into the matter, and to compel the tenants to render their accustomed services.

Humphrey de Bohun, earl of Hereford and Essex, who died in 1336, was buried in the abbey. (fn. 40)

The abbot and convent undertook under severe penalties in 1380 (fn. 41) to celebrate mass daily at the altar of the Holy Ghost in their church, for the soul of Thomas Hatfeld, bishop of Durham, except in certain specified contingencies, such as pestilence, war, or the burning of their house. In 1392 (fn. 42) they agreed to celebrate mass daily for the soul of William de Tetlyngbury, clerk, at the altar of the Holy Cross on the north side, where his body lay buried, and also at the altar of St. Mary.

When William Tyder, or Tetter, was abbot in 1521, (fn. 43) he gave a receipt by Robert Parker, a monk of the monastery, to John a Parys, father-in-law of the latter, for two sums of £20, which he had borrowed, as he had to pay the king a large sum by way of loan. A curious light is thrown on the internal history of the abbey by the statement made by Parys four years later. The abbot did this only for a policy, that his monastery might seem to the king’s collectors to be in extreme poverty. Shortly afterwards the abbot fell ill, and Parys went to Stratford to know at what point he stood for his money. Sir William Hurlestone, now abbot, showed him that the very £40 was locked up in a chest and had never been used. The abbot soon after died, and Hurlestone made labour to be abbot, and desired Parys to speak in his favour to his son-in-law, promising before certain persons that he would pay the debt, but after his election he refused to do so. (fn. 44)

Thomas, abbot of Ford, was commissioned (fn. 45) to visit the abbey and other Cistercian houses in 1535, but nothing is known of the visitation. It was probably visited by Doctor Leigh in the same year, and the £40 mentioned below may have been offered to him as a bribe. That there were dissensions in the abbey is evident from the following letter (fn. 46) of the convent to Sir Roger Chomley, recorder of London:—’ Sunday last the abbot according to the old papistical custom read a sentence among us saying he was grieved so to do, not only denouncing us accursed because of our controversy at this last visitation, discharging our conscience according to our oath to the king as supreme head of the church, but also for proclaiming it abroad, saying that we are accursed. The excommunication was procured by the general chapter beyond sea by none other authority than that of certain bishops of Rome in past years. All such excommunications are forbidden by Parliament as contrary to the king’s supremacy. Such conduct, we think, is not that of a true subject. If not, we desire you will make interest with the king that we may obtain absolution. We desire you, Master Steward, if you think it contrary to law, to show it to the visitors.’

In the same year Gabriel Donne, (fn. 47) a monk of Stratford, who had been studying at Louvain, is said to have obtained a large abbey in the west, probably Buckfastleigh.

The abbey is returned in the Valor as being worth £511 16s. 3d. yearly, the gross value being given by Speed as £573 15s. 6¾d.; though later rentals of its possessions amount to considerably more. In an account (fn. 48) of the ‘yearly increase gotten and improved in the surveying of divers the king’s purchased lands by Geoffrey Chamber, surveyor and receiver general of the said lands,’ in 29 Henry VIII, the value of the abbey is said to have increased by £96 9s. 9d. It thus survived the first dissolution, but nothing more is heard of it until 18 March, 1538, when it was surrendered (fn. 49) to the king by William, abbot; William Persouns, prior; John Merryot, chanter; John Ryddsdall, sub-prior and sacrist; Antony Clercke, bachelor; John Gybbes, Christopher Snow, William Danyell, William Peyrson, Thomas Selbey, William Symonde, John Scott, Richard Stanton, Thomas Drake and John Wryght, the last of whom could not write, and so had to make his mark. There were debts (fn. 50) or charges on its lands amounting to £276 13s. 4d., viz. to the king for rent, stuff and cattle of Stratford £110, to Stephen Vaughan 100 marks, to Dr. Leighe £40, to Stephen Kirton £40, and to others £20. The plate amounted to 279 ounces of gilt and 966 ounces of parcel gilt and white. (fn. 51) A relic, ‘said to be a piece of the Holy Cross,’ adorned with silver-gilt, was found in the abbey and delivered (fn. 52) to Cromwell on the king’s warrant. Pensions (fn. 53) were granted to all the monks except John Wryght, the abbot receiving 100 marks yearly.

An account (fn. 54) for the year following the dissolution mentions among the possessions of the abbey the manors of Burstead, Westhouse (in Burstead), Cowbrige (in Mountnessing and Hutton), Buckwynkes (in Buttsbury), Whites and Gurneys (in Burstead), Biggyn (in Chadwell), Lewisham, Beryngers (in Barking and Little Ilford), Little Ilford, Reyhouse, Eastwestham, Playce, Leyton, Eastham and Caldecote (in South Weald). The possessions were dispersed among several persons. Peter Mewtas, one of the gentlemen ushers of the privy chamber, and Joan his wife had a grant (fn. 55) in tail male on 15 February, 1539, of the reversions and rents reserved upon several leases in and about the abbey. The manor and rectory of Great Burstead and some other manors and lands were granted (fn. 56) in fee to Sir Richard Ryche on 15 July in the same year.